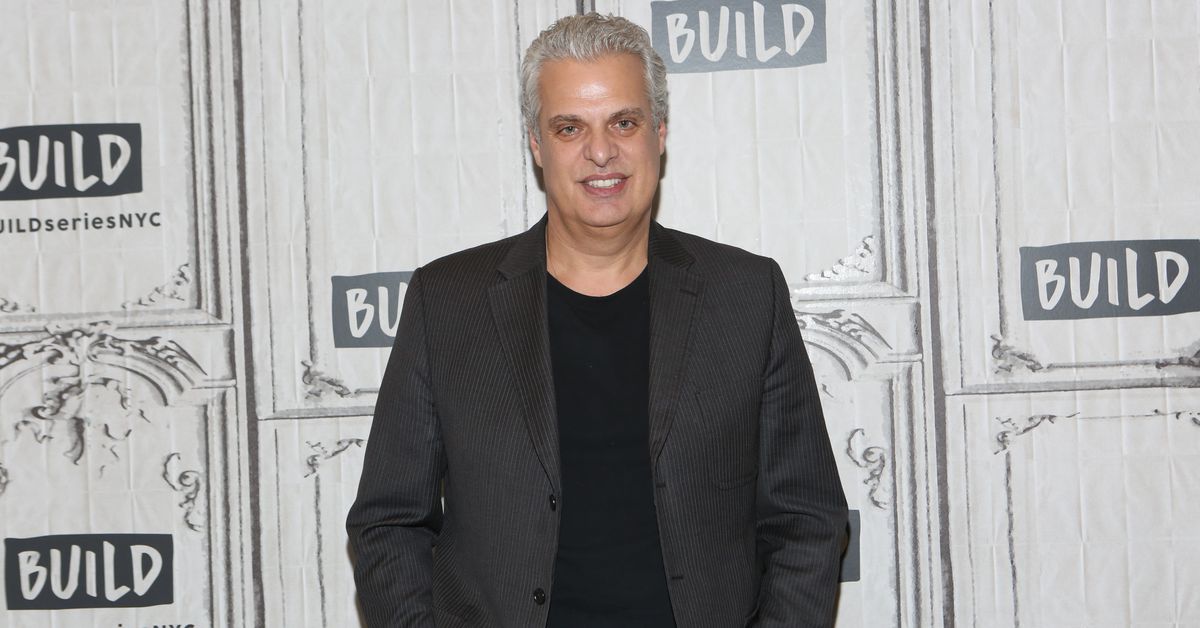

World-Renowned Chef Eric Ripert Accused of Botching ‘Pho’ Recipe, Sparking Online Backlash

Renowned chef Eric Ripert’s long-running success at his three-Michelin-starred Midtown seafood destination Le Bernardin is built on the exacting standards of classical French cooking. But when the chef took to Instagram on January 3 to post what he called a pho recipe from his latest cookbook, it sparked a wave of backlash for what appeared to be a questionable, loose interpretation of what is often considered Vietnam’s national dish.

Three days into the new year, Ripert published a post to his Instagram feed with a caption that read: “2022 HEARTWARMING DISH Vegetarian Vietnamese Pho to warm up on this cold winter day in between lunch & dinner service @lebernardinny. Swipe for the full recipe to make at home from #VegetableSimple!”

The text was accompanied by a photo of the acclaimed chef sitting at a desk in Le Bernardin’s kitchen, using chopsticks to lift strands of thin yellow noodles with one hand, while squeezing a wedge of lime over a bowl of broth, more yellow noodles, and vegetables. Subsequent slides in the post included an ingredient list and directions for making what Ripert called vegetarian Vietnamese pho, a recipe included in his book Vegetable Simple: A Cookbook, which was published in April last year.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23149400/Screen_Shot_2022_01_06_at_8.29.59_AM.png)

The first picture alone, paired with the caption proclaiming that the concoction inside the bowl was, in fact, pho, was enough to make some of Ripert’s 658,000 Instagram followers do a double take. “I thought he was eating ramen at first,” says Hung Tran, a D.C. area pharmacist and self-proclaimed ramen nerd who follows Ripert on Instagram and saw the chef’s yellow noodles when he was scrolling through his feed. Tran, who is Vietnamese, noticed the discrepancy because pho is typically made with wider, flat, white rice noodles — a signature component of the dish that didn’t appear to be present in Ripert’s bowl.

As of publishing time, the post remains up on the chef’s Instagram account with nearly 200 comments running alongside the recipe slides, with plenty of people chiming in to critique the pho photos and write-up. “Those noodles are so yellow they look like they came from a packet of instant noodles…” another commenter, @linhtrinh_nails, wrote. “And just because a lime is in the picture doesn’t mean it’s Pho.”

The chef declined through a spokesperson to comment to Eater for this story.

This is far from the first time that misguided attempts have been made to highlight pho on a wide-reaching platform, or that high-profile white chefs have misrepresented foods of other cultures by eagerly promoting interpretations that are light on cultural context and heavy on unexplained adjustments. In 2016, Bon Appétit took down a video of a white chef explaining how to eat pho, and apologized for the blunder. Blogger and cookbook author Tieghan Gerard was accused of cultural appropriation and whitewashing pho in early 2021 after posting a recipe for a chicken and noodle soup that she originally dubbed chicken pho, before changing the name following backlash in light of the recipe’s many deviations from the actual dish.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23149405/Screen_Shot_2022_01_06_at_8.30.32_AM.png)

The second photo in the Instagram post displayed a close-up shot of the dish as the image appears in the cookbook, with seemingly different ingredients, including what looked like vermicelli noodles — also not typically used for pho, Tran notes — and slices of radish fanned out in the bowl. Two more slides showed an ingredient list for a recipe labeled “Vietnamese Pho,” complete with the aforementioned radishes, soybean sprouts, soy sauce, an undefined variety of rice noodles, and a few paragraphs listing out directions for constructing the dish in about an hour. “It didn’t make sense to me,” Tran says. “It was a very weird recipe.”

Others were similarly confused by what Ripert was attempting to show with the post. Matt Le-Khac, the chef and owner of Vietnamese restaurant Bolero in Williamsburg, follows Ripert on Instagram and saw the recipe shortly after he posted. Le-Khac noted that neither noodles in the first or second photo appeared to be actual pho noodles, and he wondered why the recipe didn’t instruct users to char the broth’s aromatic spices and vegetables like onion and ginger — an integral step in coaxing out the soup’s signature, belly-warming flavors. “It’s like the quintessential smell and essence of broth in Vietnamese cuisine,” Le-Khac says.

Ripert was already riffing on the dish by making it vegetarian — classic pho is made by boiling beef bones and simmering the broth for hours to produce a flavorful, complex dish — but many chefs have toyed with pho in varying forms, including vegetarian options, and NYC is home to a wealth of standout variations. Le-Khac himself bends the rules on pho technique at Bolero, where the kitchen team uses an upscale combination oven instead of a stove to steam cauldrons of bones and water for pho and keep the broth simmering at a precise, even heat overnight — just like the one Ripert appears to be using to bake baguettes at Le Bernardin in another recent Instagram post, Le-Khac points out.

Pho itself is a relatively young invention in Vietnam that is rooted in the French occupation of the Southeast Asian country in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It’s common to see iterations on the dish, as people keep pushing it in new directions, according to Le-Khac, and Ripert is free to join in that experimentation, in his view — as long as it’s done within proper context. “We’re introducing new techniques” at Bolero, Le-Khac says. “But when we introduce it, we can’t lose the soul of the cuisine.”

Vietnamese cookbook author Andrea Nguyen, known for her James Beard award-winning cookbook dedicated to pho, The Pho Cookbook, pointed out that ingredients like radishes are not typically found in pho, and the dish is usually made with mung bean sprouts instead of soybean sprouts. “Without providing any context as to how this recipe came together and why he uses the ingredients that he uses, the [Instagram] reader is kind of like, ‘what the pho?’” Nguyen says.

Ripert’s recipe also didn’t bother to specify which type of rice noodles to buy for the soup, leaving cooks to pick from a vast range of options for a core ingredient for pho. “Let’s say I call for French bread,” Nguyen says. “What kind of French bread am I talking about? Am I talking about a baguette or a batard? Or something else?”

The fine dining chef does get into those specifics for other recipes in the book, including a French soup called an aigo boulido broth. Ripert notes the area in France that the broth comes from, its cultural significance within the region, and why he is a fan of the rich, flavorful dish. The recipe calls specifically for slices of baguette, toasted and topped with Gruyere cheese, to pair with the broth.

But Ripert doesn’t seem to extend the same careful context to the “Vietnamese Pho” recipe found later on in the book. For an internationally recognized chef with a gigantic social media presence to seemingly breeze over the core components of pho and inaccurately represent a dish of another culture felt damaging and regressive for those who understand pho’s significance in Vietnam. “I bear the responsibility in presenting the food of my culture in a very thoughtful manner — and he does, too,” Nguyen says.

In Ripert’s post, the dish labeled as pho did not appear to include the fundamentals of its namesake, and was lacking any context explaining what pho is, its significance to Vietnam, and why the chef made the changes that he did in constructing his own version of the dish. Still, the recipe was broadcast to Ripert’s more than half a million followers, many of whom left comments thanking the chef for sharing the recipe and clamoring that they couldn’t wait to try it. “This is not pho and it’s incredibly sad that so many people on this post now think it is,” one commenter, Tue Le, wrote on Instagram. “If you want to colonize or appropriate someone’s food without honoring the cultural roots of it, congratulations. You succeeded.”