A Brief History of Atlanta Restaurants’ Roles in Social Movements

The Wendy’s on University Avenue burned through the night of June 13, 2020, after suspected arsonists set fire to the building during protests on the property. The crowds were protesting police brutality following the killing of Rayshard Brooks, an unarmed Black man shot in the back while running from Atlanta police officer Garrett Rolfe. The next morning, against a backdrop of overcast skies, the charred ruins were a somber sight as people gathered at the site throughout the day. The once-pristine building now featured shards of glass and smudges of black soot. Even little Wendy, still smiling inside the logo, looked just a little less innocent.

This fire may be one of the most incendiary examples in recent history, but it’s not the first time an Atlanta restaurant was connected to a protest. There’s a long relationship between Atlanta restaurants and civil uprisings, although the reasoning and results have differed with as much range as recipes for soul food menu standards made in commercial kitchens.

During the 2020 summer protests in Atlanta, many restaurants and bars stood with those demanding justice for George Floyd, and then Brooks. Several restaurants, such as Summerhill Thai spot Talat Market and Koinonia Coffee ATL, a former coffee shop in southwest Atlanta, donated proceeds to the Atlanta Solidarity Fund and similar groups providing bail funds and pro-bono legal assistance to protesters. Now, in a moment informed by recent years’ protests, marked by overlapping social and global crises, and braced for the lead up to another state election that will prompt further political engagement from restaurants and residents across Atlanta, it’s even more crucial to revisit the city’s political legacy. The work to achieve an equitable society for all is ongoing and never finished.

Atlanta’s trailblazing culinary canon

Akila McConnell, author of A Culinary History of Atlanta, says there’s an established legacy of local restaurants championing or involving themselves in social justice movements and politically controversial issues. In the 1960s, McConnell says, Joe Rogers Sr., co-founder of Waffle House, welcomed Black protesters demonstrating outside the former Midtown location of the all-day breakfast chain. Around the same time, Lester Maddox, an avowed segregationist who later became governor of Georgia, chose to shut down his Pickrick Restaurant rather than comply with the 1964 Civil Rights Act and allow Black patrons to dine there. He went so far as to block the restaurant’s entrance while brandishing a pistol. Maddox ended up closing the restaurant rather than integrate it under the new law.

For McConnell, understanding Atlanta restaurants’ relationships with social justice and advocacy requires understanding the city’s beginnings, starting with Ransom Montgomery in the late 1840s. Montgomery would become the second Black person in Atlanta to own property, open a small but widely impactful food stand, and establish himself as what McConnell calls “Atlanta’s first restaurateur.”

After he saved the lives of 100 passengers on a train headed toward a burning bridge over the Chattahoochee River in 1849, the Georgia legislature rewarded Montgomery by purchasing him from a white man, making him the only enslaved person to ever be legally owned by the state. He was also given a plot of land near the roundhouse for the Macon train line, where he was allowed to sell coffee and cakes from a little shop. Montgomery’s food stand helped him and his brother Andrew found Atlanta’s oldest Black church, Big Bethel AME on Auburn Avenue.

About 170 years later, on June 20, 2020, the church was the site of a protest condemning the killings of Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and George Floyd — led by the families’ attorney, Ben Crump, and the members of Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Inc.

McConnell also points to other Atlantans who turned food profits into community-building assets, like Evelyn Jones Frazier, a Black woman restaurateur who opened Frazier’s Cafe Society in 1946. Frazier’s was one of Atlanta’s first Black-owned restaurants to provide an elegant dining experience, and hosted fundraisers and meetings for civic and political activism. Then, there’s James Tate, who McConnell refers to as “the father of Atlanta’s Black business.” Tate became a wealthy man in the latter part of the 19th century by turning a sandwich-selling grocery store into a real estate business that helped him open Atlanta’s first Black elementary school. He was also a founding member of Friendship Baptist Church, where historically Black colleges Morehouse and Spelman began in the basement. Since then, students from the colleges have organized and participated in protests and social justice movements for decades, both in the U.S. and around the globe.

“Right from the beginning, that was the Atlanta way,” says McConnell. “The earliest restaurateurs felt like they had to give back to their community. And I think it’s always been that way […] Protest is a way of ensuring that your community succeeds. So, to me, I feel like this is part of our makeup as ATLiens. This is who we are.”

Civil rights and the endured wrongs

The civil rights movement is the most widely referenced example of Atlanta restaurants publicly supporting protests, demonstrations of civil disobedience, and other demands for justice. Starting in the late 1950s, leaders regularly organized and planned demonstrations, protests, marches, sit-ins, and other forms of nonviolent confrontation around the South. Often these plans materialized while dining at Black-owned restaurants southwest of downtown Atlanta. But oftentimes, textbook accounts of this era understate the crucial role restaurants served as political incubators and movement catalysts.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23342227/Eater_National_Feeding_The_Resistance_Mocm_Ups_0000_Original_Busy_Bee.png)

As the owner of soul food institution Busy Bee Cafe on the edge of the Vine City neighborhood, Tracy Gates knows this legacy well. According to Gates, the origins of Busy Bee date back more than 40 years before it opened to the bloody, multiday Atlanta Massacre of 1906. During the massacre, white mobs, angered by unsubstantiated reports of Black men sexually assaulting white women, murdered and maimed African Americans in Atlanta, destroying their property and livelihoods in the process. As a result, Black entrepreneurs left downtown Atlanta and created new business districts in nearby neighborhoods, including the historic West End, Sweet Auburn, and Vine City, just west of where Mercedes-Benz Stadium now sits.

It was in Vine City on Hunter Street (now Martin Luther King Jr. Drive) that self-taught chef Lucy Jackson entered the restaurant industry, eventually opening Busy Bee Cafe. Jackson earned a reputation for serving consistently delicious fried chicken and ham hocks paired with welcoming hospitality that drew civil rights leaders Ralph David Abernathy, Hosea Williams, Jesse Jackson, Andrew Young, Joseph Lowery, and King to her table.

The evolution of an epicenter

Leaders of the civil rights movement also frequented Paschal’s restaurant, a Black-owned establishment adjacent to the Atlanta University Center (AUC) similarly known for its inclusive hospitality and its fried chicken. It, too, once resided on Hunter Street before moving east to the Castleberry Hill neighborhood. Opened in 1947, Paschal’s was founded by brothers James and Robert Paschal. The brothers would eventually partner with Herman J. Russell, a self-made millionaire who built a construction and real estate empire and became one the most influential Black businessmen in Atlanta.

Longtime customer Charles Black remembers when he and other students from the historically Black colleges in the AUC planned demonstrations at Paschal’s in the 1960s. Black was one of eight students (along with Julian Bond) who took a class led by King when he taught a semester of social philosophy at Morehouse College. Black was chairman of the Atlanta Student Movement and would become lifelong friends with civil rights icon and Georgia congressman John Lewis and the movement’s founder Lonnie King.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23342230/Eater_National_Feeding_The_Resistance_Mocm_Ups_0003_Paschals.png)

Back in his organizing days, James Paschal saw Black with a diverse group of young activists enjoying drinks one evening inside La Carrousel, the restaurant’s former jazz club on Hunter Street. Paschal pulled Black aside and asked him to verify his guests were of legal drinking age. Then he made a request. Despite the fact that La Carrousel was famously desegregated, he wanted Black and his party to separate.

La Carrousel, Black says, had received a rare license from the city of Atlanta to serve alcohol. But, the license came with strings: additional scrutiny that could not only jeopardize Paschal’s license and financial stability, but also result in violent retaliation that could potentially jeopardize the very crowds of lively clubgoers.

“Paschal had a license that nobody else in town had. It was a privilege license. He could serve alcohol, mixed drinks, without you being a member of a club […] During those days, you either had private clubs, or you had some places that had pouring licenses, but you had to bring your own booze,” Black says. “He asked that I request that the Black guys not sit with the white girls, and he reminded me of his privileged license, which [Paschal believed] would be taken away from him.”

Black went back and told the party they needed to separate. Despite being angry, the group accommodated Paschal’s request. Black says the next day his friends wanted to picket Paschal’s, but he talked them out of it, insisting they focus on an ongoing voter registration campaign. His success in cooling the students earned him a gift from Paschal: an undated membership card to La Carrousel to come back and see any jazz show, free of charge.

“When we went to jail,” Black adds, “Paschal would keep the restaurant open until we got out. We could go there and eat some fried chicken and get potato salad for free […] That was special.”

The Russell family operates Paschal’s today, both in Castleberry Hill and at Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport, through the family-owned company Concessions International, which operates more than 40 food and beverage brands in eight domestic airports.

Mori Russell, Herman Russell’s granddaughter, is the company’s business development manager, and says the importance of Paschal’s as a long-established meeting place in Atlanta for civil rights leaders and organizers cannot be overstated.

To remind customers of the restaurant’s role in the civil rights movement and present-day causes, Paschal’s features photos of Black leaders on the walls, from the spacious main dining room to the private meeting room named for Maynard Jackson, Atlanta’s first Black mayor.

Mori sees the mission of Paschal’s and Concessions International as multifaceted. By running successful hospitality businesses, her family helps fund actions which benefit those who’ve endured social and economic injustices and can expand into bigger missions taking place across the street from Paschal’s at the Russell Center for Innovation and Entrepreneurship, which provides resources to Black-owned businesses and entrepreneurs.

“That’s really where we’re working […] as a family and making sure that we provide a place to create a better economic stance for our people. Because we see that as a way to advance education and success — a way to get ahead. […] Our family is in support of peaceful protesting and standing up for our rights. We started with the protests; now, it’s time for strategy. We want to be leaders in doing that.”

Gates, too, wants Busy Bee’s success to help fund businesses and organizations pushing for equity and social justice. She donates regularly to BeLoved Atlanta, a residential program for women who have suffered sexual exploitation headquartered nearby in Vine City. Gates now checks in with her staff to help keep them engaged with local and social justice causes and ways to effect needed changes within their own communities.

The next generation

Even before the protests in 2020, a new generation of socially conscious and politically active restaurateurs and Atlanta residents were taking to the streets to demand changes to outdated social and political constructs.

Georgia Beer Garden and Noni’s in Sweet Auburn frequently host public events for political candidates running for local and state offices. Noni’s has even hosted texting and letter-writing campaigns to get out the vote during crucial election cycles.

Some restaurants prefer quiet financial donations. Others are famously overt with activism despite the risks that come with it, from potential revenue loss and social media critique to outright pickets, vandalism, and more. Still, some restaurants use their undisguised activism to create new communal rallying points, like Sister Louisa’s Church, the outrageous bar located off of Boulevard where a crowd gathered under its mural of Stacey Abrams after Joe Biden was elected president, just steps from the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historical Park.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23342229/Eater_National_Feeding_The_Resistance_Mocm_Ups_0002_Sister_Louisa_s.png)

Grant Henry, owner of Sister Louisa’s, said in a text that he commissioned the Abrams mural in 2018 because he believed Georgia was “in pretty bad shape.” He says he’s offered the space for voter registration drives during recent election cycles. Other murals have since appeared on the exterior walls of the bar, highlighting present-day social justice leaders and civil rights activists, including former NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick and former President Jimmy Carter.

Slutty Vegan owner and Clark Atlanta University alum Aisha “Pinky” Cole founded the Pinky Cole Foundation, a nonprofit organization focused on empowering Black entrepreneurship. She and Big Dave’s Cheesesteaks owner Derrick Hayes partnered to purchase a car for Tomika Miller, the widow of Rayshard Brooks. Cole also provided life insurance policies and scholarships for Brooks’ four children to Clark Atlanta University.

Atlanta entrepreneur and activist Latisha Springer launched the grassroots mutual aid organization Free99Fridge in 2020 to combat food insecurity within the city’s rapidly gentrifying neighborhoods. After opening community fridges at Best End Brewing in the West End and Hodgepodge Coffeehouse in East Atlanta, Springer is now expanding the operation, partnering Free99Fridge with the Grocery Spot to launch a pay-what-you-can mutual aid grocery store on Charlotte Place in Grove Park. She recently relocated the two community fridges at Best End to the old farm stand outside Aluma Farm in the southwest Atlanta neighborhood of Oakland City.

Community activism is built into the business model at Our Bar ATL on Edgewood Avenue. Its multiple owners, who have all worked in the restaurant industry, pooled their money together to create Our Bar, which opened just days before the start of the pandemic in March 2020. Partner Sarah Oak Kim says the space naturally evolved into a hub, not just for Atlanta’s nightlife culture, but for cause-based community service.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23342238/Eater_National_Feeding_The_Resistance_Mocm_Ups_0009_Our_Bar_1.png)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23342233/Eater_National_Feeding_The_Resistance_Mocm_Ups_0005_Our_Bar_2.png)

Throughout those first few weeks of the pandemic, the Edgewood Avenue bar owners fed and collected goods for their unhoused neighbors, hosted pop-up kitchens for out-of-work chefs, and allowed creatives to use the space, from bands needing places to practice to vendors selling clothing and art. When the 2020 summer protests hit, they provided water for demonstrators and hosted panel discussions with elected leaders and political candidates, held voter registration drives, and facilitated conversations between police and the community.

Partner Shawn Rolison invited members of the Atlanta Police Department to speak to an audience at Our Bar. “Being a Black male, but also working in a security capacity, I overstood the disconnect between law enforcement and Black men,” he says. “It wasn’t until just recently that I realized, damn, we can be part of the solution. That’s what made me want to do the panel.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23342231/Eater_National_Feeding_The_Resistance_Mocm_Ups_0004_Our_Bar_3.png)

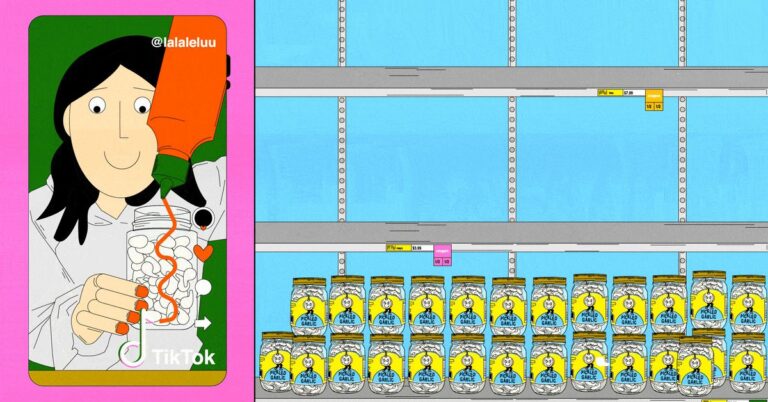

During the 2018 Georgia general election, a grassroots group called #ProtestPizzaATL raised nearly $2,500 to purchase and provide pizza and snacks to voters experiencing long lines at the polls. The group was born out of anger and frustration after the 2018 primary in Georgia earlier that year made national news when footage went viral of people waiting in hours-long lines to cast ballots around Atlanta.

In 2020, Adelaide Taylor, #ProtestPizzaATL leader, says the group partnered with Summerhill pizzeria Junior’s Pizza and raised more than $11,000 in five days through social media, of which nearly $7,900 was donated to Fair Fight Action, an organization battling voter suppression founded by Georgia gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams.

Jennifer and Alex Aton, the owners of Junior’s Pizza, say they continue to speak out against voter suppression in Georgia and act in solidarity with social justice advocates in the community, from statements supporting the “defund the police” movement to harshly criticizing Gov. Brian Kemp on the night District 58 state representative Park Cannon was arrested for knocking on his office door. With 2022 being a crucial election year in Georgia, the couple anticipate finding ways to again become involved in efforts to get out the vote in Atlanta.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23342226/Eater_National_Feeding_The_Resistance_Mocm_Ups_0000_Atons.png)

Like the Atons and Taylor, journalist and filmmaker King Williams was one of several Atlantans whose actions during the 2020 election cycles are now illegal in Georgia. In 2020, Williams went to several polling places throughout Atlanta giving out free pizza to voters waiting in line. An overhaul of the election laws signed by the governor in 2021 now forbids passing out food or drink to voters at polling stations, which many voting rights advocates believe directly impacts low-income and Black voters in Georgia.

“Like many laws […] it’s a solution in search of a problem,” he says. “Myself and other people were giving out food and things like that at the post because the secretary of state was making it hard to vote.”

Williams says he became an unofficial one-man Domino’s pizza delivery agent after personally witnessing voting delays during the 2020 primary. While trying to help a disabled voter at Barack H. Obama Elementary Magnet School of Technology find her proper polling place after she was told she’d come to the wrong location, Williams said the line never stopped growing. Being from the Gresham Park area, he knew a Domino’s was less than a mile away.

“I got on Twitter, like, ‘Hey, if anybody wants to donate pizza…’ Then, I just ordered a bunch of pizza from Domino’s. And I just kept doing it.” At one point, Williams had 50 pizzas in the back seat of his car. Before the end of the day, he’d dropped off free slices to voters from Reynoldstown in Atlanta to Union City, nearly 20 miles southwest of the city.

Williams insists the changes in the law won’t stop him from helping voters in 2022, because if the system worked properly, he says, food donations wouldn’t be necessary. The governor, secretary of state, and attorney general are among the nine state executive offices up for election in Georgia this year. The election will also decide the fate of the Senate seat currently held by Raphael Warnock, who first took office in 2021.

“This year is the Super Bowl of Georgia elections. People like myself are going to be more prepared to make sure people’s needs are met.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23342236/Eater_National_Feeding_The_Resistance_Mocm_Ups_0007_John_Lewis.png)

Busy Bee’s Gates believes it’s necessary for people to continue speaking out now. She’s seen signs over the last five years leading her to fear the country may be backsliding toward the separatist status quo of the 1960s. But Gates also says she’s felt buoyed by the similarities in the efficacy of present-day protests to the civil unrest, marches, and organizing done at Atlanta restaurants in the 1960s. To her, Busy Bee Cafe can still impact change.

“I understand now what that ’60s movement meant — I don’t understand the segregation part of it, but I understand the community part of it, how they were able to thrive […] and how integration came,” she says. “In this sacred, hallowed spot, I understand it. And now it’s more prevalent than anything.”

Mike Jordan is an Atlanta-based multimedia journalist and editor-in-chief at Butter.ATL, a media company dedicated to the dynamic culture of Atlanta. He’s also the southeast editor of content at Resy, a newsletter columnist for the Local Palate, and a frequent contributor at the Wall Street Journal, the Guardian, Atlanta magazine, Playboy, Rolling Stone, and Eater Atlanta, where he regularly writes about food, business, entertainment, technology, politics, and more.

Fact checked by Hanna Merzbach

Photo collages by Nat Belkov

Photography by Ryan Fleisher

Additional photography by Busy Bee Cafe and Our Bar ATL