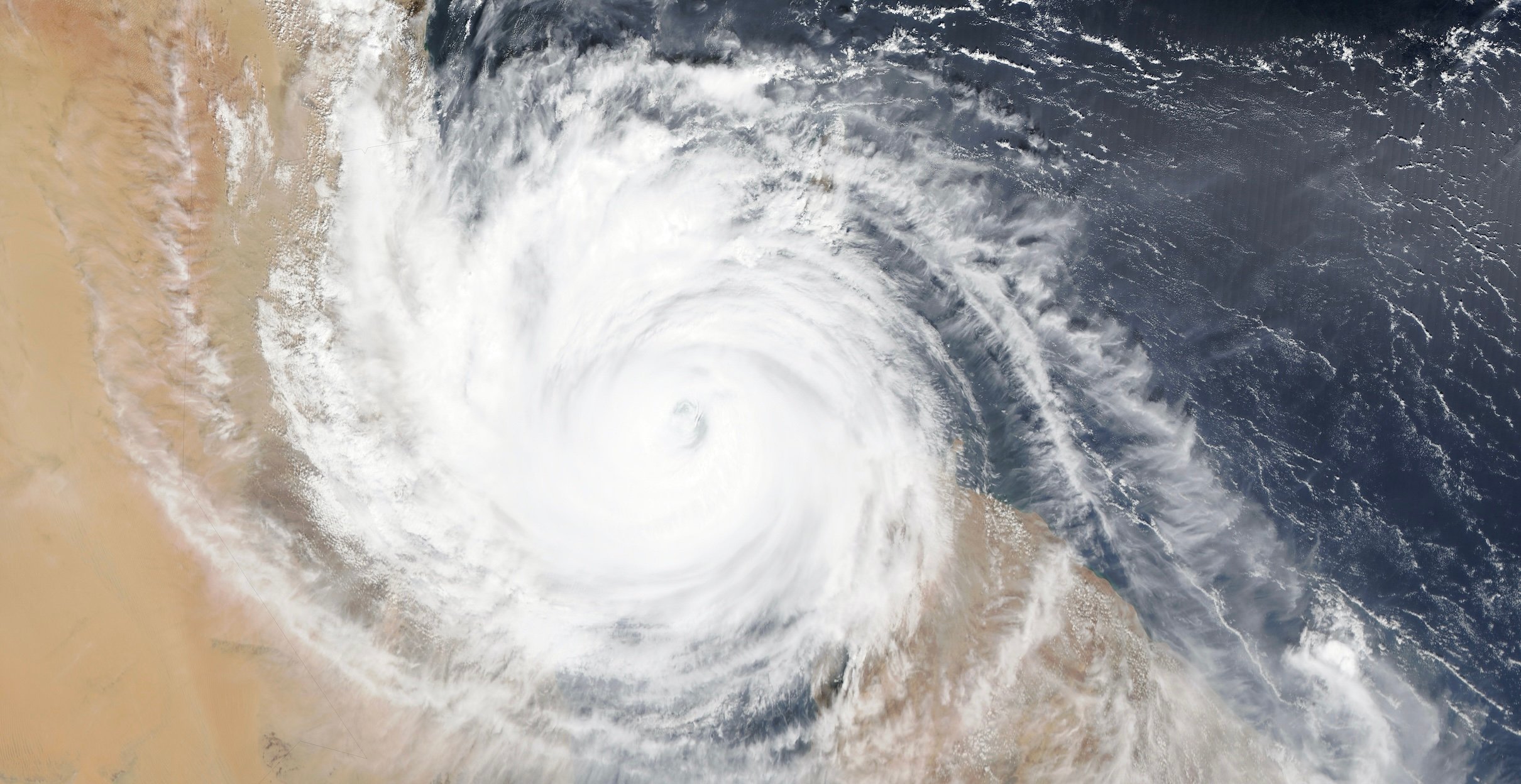

New Government Study Finds Cleaner Air Leads to More Atlantic Hurricanes

A new study conducted by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), a federal agency focused on the condition of the oceans and the atmosphere, found that cleaner air is leading to more hurricanes.

The study was written by Hiroyuki Murakami and published in Science Advances on Wednesday, a peer-reviewed multidisciplinary open-access scientific journal.

“A 50% decrease in pollution particles and droplets in Europe and the U.S. is linked to a 33% increase in Atlantic storm formation in the past couple decades, while the opposite is happening in the Pacific with more pollution and fewer typhoons,” AP reported.

Here is the abstract:

Over the past 40 years, anthropogenic aerosols have been substantially decreasing over Europe and the United States owing to pollution control measures, whereas they have increased in South and East Asia because of the economic and industrial growth in these regions. However, it is not yet clear how the changes in anthropogenic aerosols have altered global tropical cyclone (TC) activity. In this study, we reveal that the decreases in aerosols over Europe and the United States have contributed to significant decreases in TCs over the Southern Hemisphere as well as increases in TCs over the North Atlantic, whereas the increases in aerosols in South and East Asia have exerted substantial decreases in TCs over the western North Pacific. These results suggest that how society controls future emissions of anthropogenic aerosols will exert a substantial impact on the world’s TC activity.

You can read the rest of the study here.

More from AP:

NOAA hurricane scientist Hiroyuki Murakami ran numerous climate computer simulations to explain change in storm activity in different parts of the globe that can’t be explained by natural climate cycles and found a link to aerosol pollution from industry and cars — sulfur particles and droplets in the air that make it hard to breathe and see.

Scientists had long known that aerosol pollution cools the air, at times reducing the larger effects of greenhouse gases from the burning of fossil fuel and earlier studies mentioned it as a possibility in increase in Atlantic storms, but Murakami found it a factor around the world and a more direct link.

Hurricanes need warm water — which is warmed by the air — for fuel and are harmed by wind shear, which changes in upper level winds that can decapitate storm tops. Cleaner air in the Atlantic and dirtier air in the Pacific, from pollution in China and India, mess with both of those, Murakami said.

In the Atlantic, aerosol pollution peaked around 1980 and has been dropping steadily since. That means the cooling that masked some of the greenhouse gas warming is going away, so sea surface temperatures are increasing even more, Murakami said. On top of that the lack of cooling aerosols has helped push the jet stream — the river of air that moves weather from west to east on a roller-coaster like path — further north, reducing the shear that had been dampening hurricane formation.

“That’s why the Atlantic has gone pretty much crazy since the mid-90s and why it was so quiet in the 70s and 80s,” said climate and hurricane scientist Jim Kossin of the risk firm The Climate Service. He wasn’t part of the study but said it makes sense. The aerosol pollution “gave a lot of people in the 70s and 80s a break, but we’re all paying for it now.”

While aerosol cooling is maybe half to one-third smaller than the warming from greenhouse gases, it is about twice as effective in reducing tropical cyclone intensity compared to warming increasing it, said Columbia University climate scientist Adam Sobel, who wasn’t part of the study. As aerosol pollution stays at low levels in the Atlantic and greenhouse gas emissions grow, climate change’s impact on storms will increase in the future and become more prominent, Murakami said.

In the Pacific, aerosol pollution from Asian nations has gone up 50% from 1980 to 2010 and is starting to drop now. Tropical cyclone formation from 2001 to 2020 is 14% lower than 1980 to 2000, Murakami said.

Murakami also found a correlation that was a bit different heading south. A drop in European and American aerosol pollution changed global air patterns in a way that it meant a decrease in southern hemisphere storms around Australia.

Read more here.